My trip from the FCT to the Southwest last December was largely uneventful. A day before, I had called Akeem, a trusted cab driver, to pick me up at my residence at 5 am the next day so that I could join the first vehicle leaving Abuja for Ile-Ife, which was my destination. Ordinarily, at 5 am, I could have easily hailed a cab just a few metres away from my residence but of the series of security reports on the escalating growth of petty and violent crimes in Abuja made me choose the more costly alternative.

As we made our way out of the city through the lone road covered in the dark shades of the night that was gradually dawning into a new day, I kept looking around for the presence of security patrol vehicles. When I asked the driver about the security of the lone road, he smiled and reminded me that security is solely in the hands of God.

Luckily, the day got bright quite early and the road got busier allaying some of my fears about the road that was devoid of security presence despite the recently reported cases of insecurity along the same road. Despite the few undulating portions of the road and the much fewer dusty patches, the driver advanced with amazing speed that at around 9 am, we were already in Kogi State.

The first interruption we experienced in the course of the trip was in Kogi where we noticed that a group of young men had created a diversion and were attempting to control the traffic in a very uncoordinated and irritating manner. While the driver carefully made his way through the group that appeared like a mob, I forced myself to believe that those young men were only trying to raise funds possibly for a carnival rather than connect it to the incidence of post-election violence that had been reported in the state just a few weeks earlier.

At the end of the diversion, however, was one of the most horrible sights I have ever seen. About four persons laid dead covered with banana leaves and sacks. Young men helped to cover fresh flows of human blood with sand. Women watched from a distance, with sobering looks and blind gazes. Immediately, I lost my appetite for my favourite decently prepared pounded yam, egusi, and bushmeat that I was already planning to buy at Kabba that was just a few kilometres away.

The gory sights at Kogi reminded me once again of the hodophobia I developed due to the many unimpressive reports about road trips in Nigeria. Just like the many documented cases of kidnapping and armed robbery along Nigerian highways, the accident I had seen was just another piece of statistics.

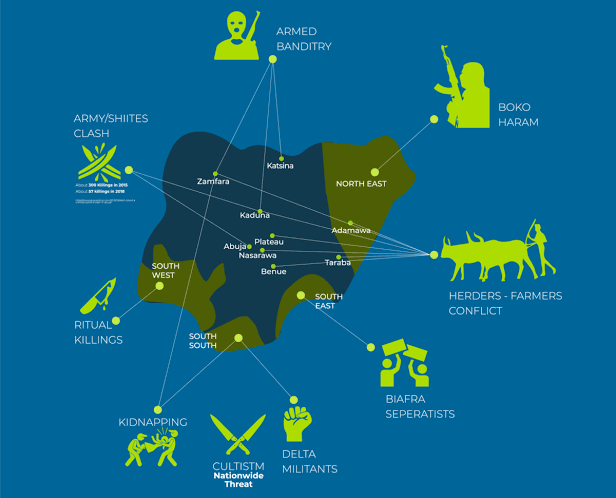

Beyond the failing security and safety along Nigerian highways, kidnapping, terrorism, crude oil theft, armed robbery, car snatching, and other sundry crimes are widespread across the country. For instance, the police reported 685 cases of kidnapping just in the first quarter of 2019 alone. By implication, an average of seven people kidnapped daily within the period. Farmer-herder conflicts, particularly in the middle belt region, killed more than 3,600 people between 2016 and 2018. Similarly, Boko Haram insurgency has displaced over two million people in the northeast of Nigeria.

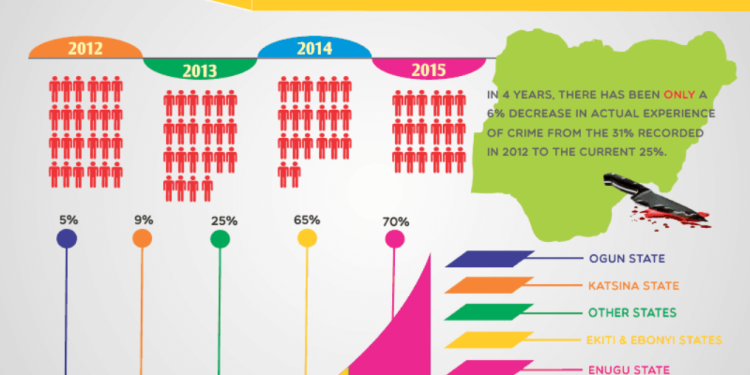

While the security situation in Nigeria is frightening, the huge investment into the security sector without commensurate returns continue to raise serious questions. For instance, despite an investment of over ₦4.61 trillion into the security sector between 2012 and 2015, only a 6% decrease in the actual experience of crime was recorded with the same period.

In the 2019 budget, the combined allocation to the security sector is over ₦1 trillion. In spite of the enormous allocation to the sector, it does not make its spending public, making it difficult to track the nation’s investment in the sector. In an article by Premium Times in 2015, it was reported that this absence of disclosure in the security sector makes the sector the most prone to contract inflation and ineffective service delivery in the country.

In the 2019 budget, the combined allocation to the security sector is over ₦1 trillion. In spite of the enormous allocation to the sector, it does not make its spending public, making it difficult to track the nation’s investment in the sector. In an article by Premium Times in 2015, it was reported that this absence of disclosure in the security sector makes the sector the most prone to contract inflation and ineffective service delivery in the country.

Insecurity in Nigeria comes at different costs. A cost might be in health deterioration for apprehensive road travellers who cannot afford other means of transport, especially for unaffordable trips. Another cost is the direct losses of human lives, valuables, and properties to insecurity in the country. Of course, the implication of insecurity to investment (local and foreign) is a cost that cannot be neglected. Proshare documented that insecurity in Nigeria has devastated agricultural production, limited economic growth, and caused significant detrimental impacts on public infrastructure such as schools, hospitals, and bridges.

It is plausible to submit the cost of insecurity in Nigeria is the extent to which a country with a very high debt profile continues to commit very significant portions of its revenue into the unaccountable security sector without imposing accountability measures. This cost also includes the implications of allowing the grossly inadequate revenue allocation to national security to fall into a few hands. It includes the unavailability of security operatives at places with high-security risks either through under-staffing or negligence. The cost is also in the growing sentiments about road trips in a country with enormous tourism potentials.

In addition, the cost of insecurity includes the value placed on human life in the country. It is the failure of the Nigerian government to develop robust policies to address the fast-growing menace. The cost also covers the threats posed by this menace to peaceful electoral transitions in the country. Ultimately, the cost is the disposition of the Federal Government to worrisome trends of fund diversion in the security sector.