Nigeria is Africa’s largest economy with a gross domestic product (GDP) of $448 billion. However, its stock market capitalisation is considered too small for an economy of that size.

For the stock market, size matters. The bigger the market, the merrier. Investors enjoy a big stock market as it enables them to trade several instruments and derive high returns on investments. A big stock market also deepens the economy and delivers growth, analysts say.

The stock market is also known as the equities market. Investors buy shares and become part of the firms’ ownership, receiving dividends quarterly, half yearly or annually.

For Nigeria, the stock market cap is estimated at $63 billion (N29 trillion), which is just 15 percent of the GDP. For starters, market cap or market capitalisation is the total value of all the companies’ shares that are being traded. According to Investopedia, an online economic dictionary, a stock market-to-GDP ratio that is above 100 percent is an indication that the market is overvalued, but it also shows positive performance. However, a market between 50 percent and 75 percent shows the market is moderately undervalued. A market below 50 percent means it is highly undervalued.

Nigeria’s market cap-to-GDP for Nigeria is 15 percent, indicating that it is tremendously undervalued and under-performing. Analysts believe it is a barometer that shows Nigeria’s poor economic performance.

“Nigeria’s stock market has very few instruments and is still very small,” said a Lagos-based investment banker, Mr Innocent Unah. “It requires confidence of investors to boom, which is not yet there,” Unah told Dataphyte.

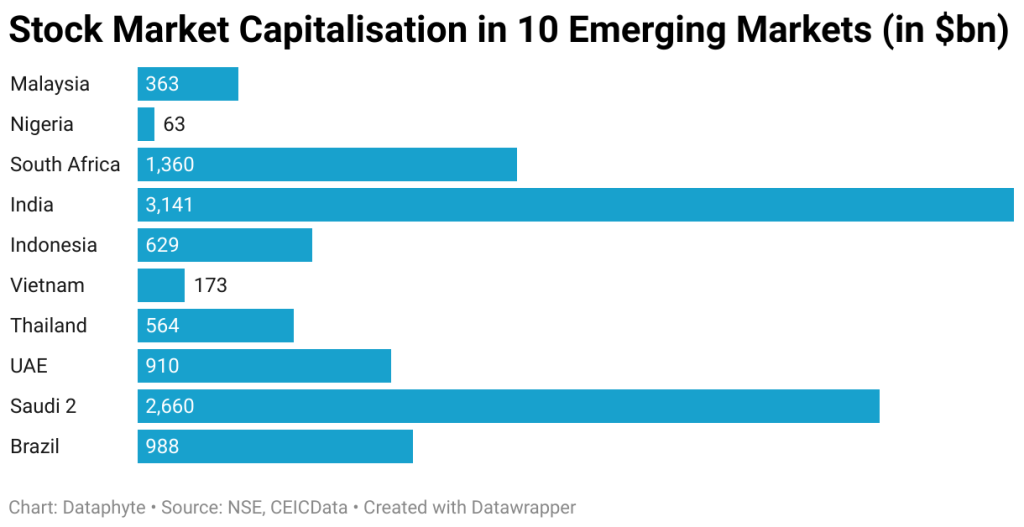

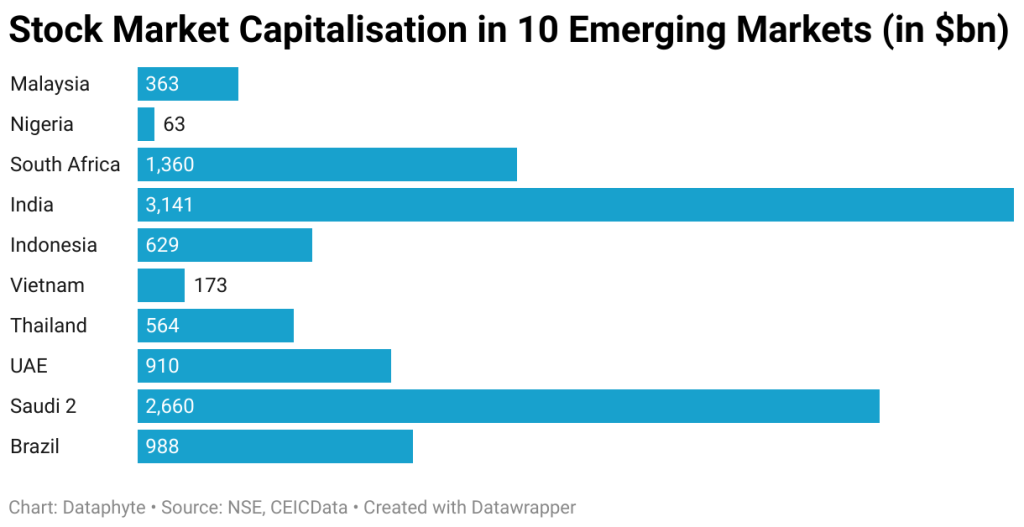

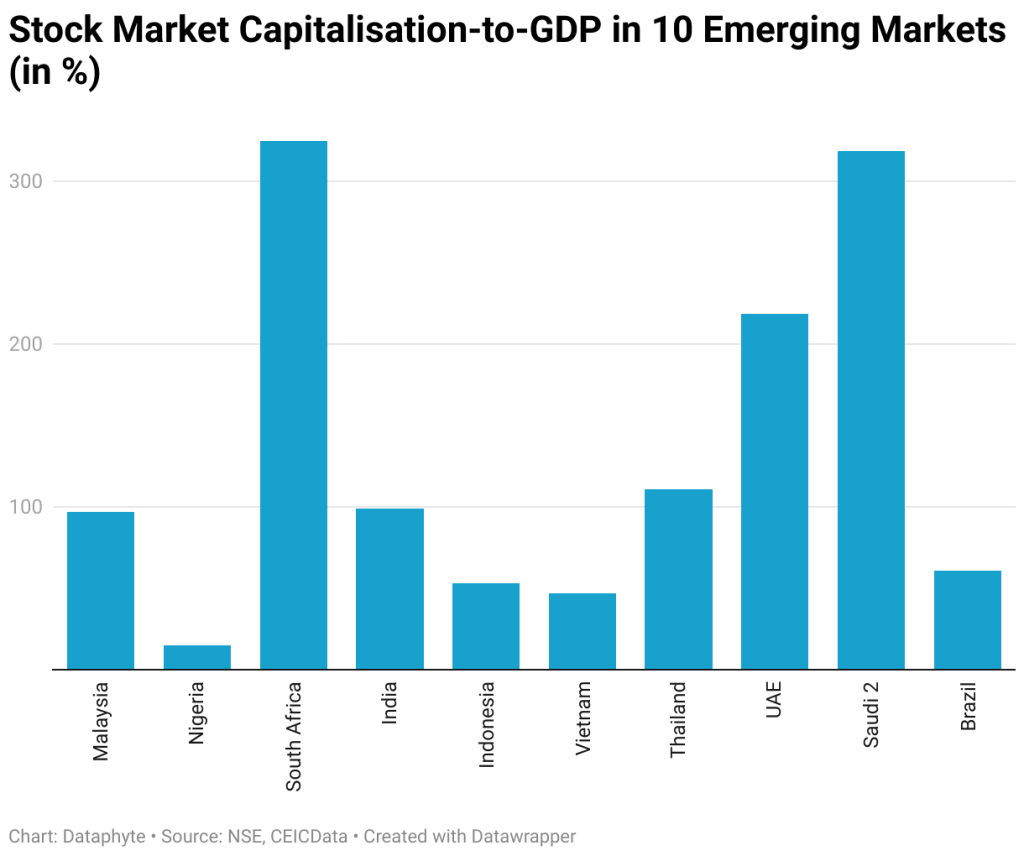

Other EMs are performing better

Many emerging markets are performing far better than Nigeria. An example is South Africa, the continent’s second largest economy with GDP of $418 billion. It has a atock market cap of $1.36 trillion, making it one of the top 20 performers in the world. This represents 325 percent of the country’s GDP, meaning that South Africa’s stock market is bigger than its GDP – a case of overvaluation but exciting performance.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has a market cap of $910.131 billion, while Brazil’s is $988.37 billion. For another emerging market, Thailand, its stock market cap is estimated at $563.90 billion, while Malaysia’s is $362.96 billion.

Saudi Arabia, whose oil firm Aramco reported $161.1 billion in 2022, has a stock market size of $2.66 trillion as against Vietnam’s $172.82 billion.

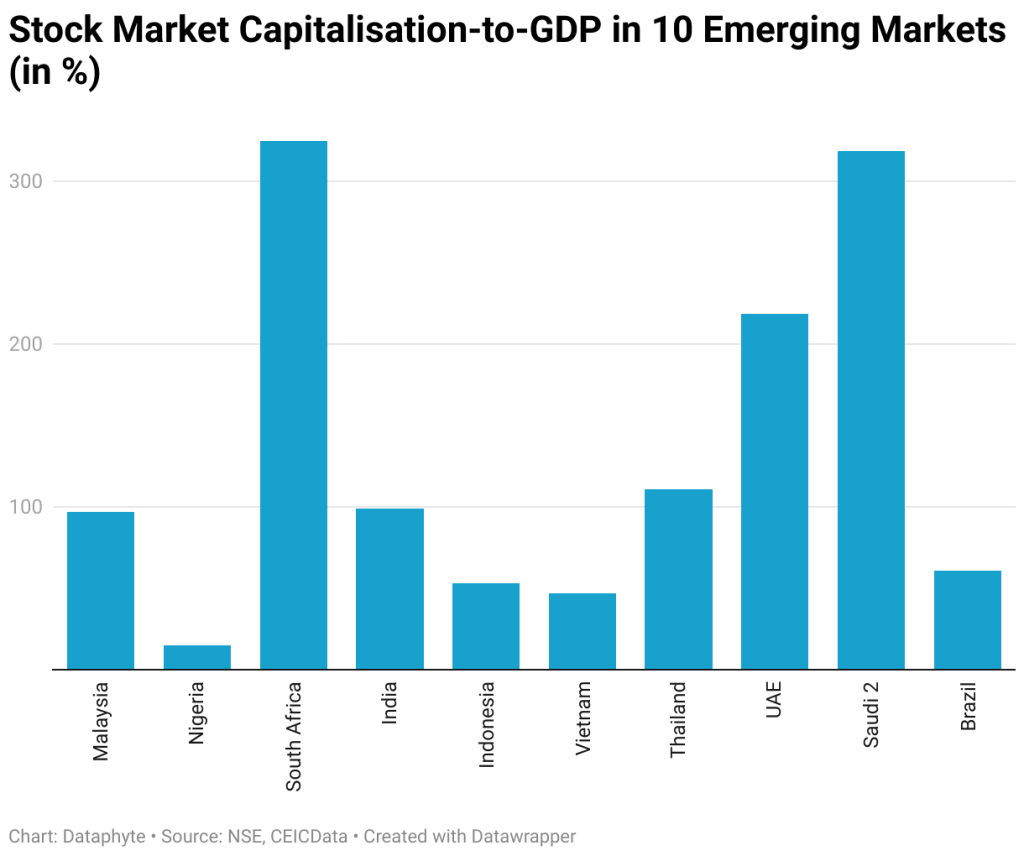

Stock cap-to-GDP ratios

Stock market-to-GDP ratio, also called the Buffet Indicator, weighs the percentage of the stock market value to the GDP. It was named after the Oracle of Omaha, Warren Buffet, in 2011, after stating in an interview that “it is probably the best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment,” as quoted by Longerntrends.net. It is not the only method of assessing stock market performance, but it is a reliable measure.

It is obtained by dividing the stock market cap by the GDP. Nigeria’s stock market cap-to-GDP is 15 percent but Saudi’s is 319 percent. South Africa’s ratio is 325 percent, whereas Thailand’s is 111 percent. The UAE is 219 percent while Brazil’s is 61 percent. India’s is 99 percent while that of Vietnam is 47 percent. Indonesia’s is 53 percent just as Malaysia’s is 97 percent.

Economists believe that a stock cap-to-GDP of over 100 percent is overvalued while that between 50 percent and 75 percent is moderately undervalued. A number between 76 percent and 99 percent is properly valued. On the other hand, a number below 50 percent is so much undervalued. The data therefore show that the Nigerian stock exchange is so much undervalued and an underperformer, being the least of all the emerging markets being examined.

It is also an indication that many economic agents are not participating in the market or, at least, leveraging its opportunities.

Why is Nigeria’s stock market too small?

Market analysts say that one of the major reasons for the miniature size of the Nigerian stock exchange is lack of attractiveness. South Africa boasts of companies with large market caps such as BHP, Prosus, Ab Inbev, Richemont, among others. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) has about 400 listed companies on its equities market while Nigeria’s stock market has 177 firms on the bourse, according to Statista, a data and research firm.

.webp)

However, it is not so much about the number of listed firms but the quality of companies on the bourse. Even though Nigeria has 177 companies listed on its bourse, the total market cap is just $63 billion. Abu Dhabi (UAE) Stock Exchange has only 73 companies listed on its bourse but they are worth $910 billion in total. Saudi has 207 firms listed on its market – a little above Nigeria. However, its market cap is $2.66 trillion. Saudi’s listed companies include deep-pocket firms such as Saudi Aramco, Al Rajhi Bank, SABIC, among many others. These three companies’ market caps are 37 times Nigeria’s market cap and at least five times bigger than Nigeria’s GDP.

Analysts wonder why the Federal Government cannot list its oil company, the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation Limited (NNPCL), and get other deep-pocket firms to list. Getting large companies to list increases the total market capitalisation and boosts the economy, economists argue.

“The market needs to be attractive enough to get the companies to list,” a stock broker and Executive Vice-Chairman of Highcap Securities Limited, Mr David Andori, told Dataphyte.

Former stock broker and Country Manager of Spectra Ink Nigeria, a fintech firm, Mr Ayotunde Alabi, said many firms did not find it necessary to list on the stock market because they would always be able to raise funds through bonds or other means.

“You do not need to be in the stock market to raise funds. You can issue bonds or commercial papers and raise funds. So, tell me, why should you list on the bourse with all of its problems?” he asked.

The dwindling economy

Average economic growth in Nigeria has been below 3 percent in the last eight years. Growth was merely 3.1 percent in Nigeria in 2022, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. Nigeria is not the worst performer among the 10 emerging markets being examined but it is surely a laggard. Though it dwarfs South Africa’s 2.1 percent and Brazil’s 2.8 percent GDP performance in 2022, it lags Saudi and Malaysia’s 8.7 percent growth and Vietnam’s 8.0 percent economic performance.

.webp)

In fact, it is fourth from the bottom. Economic or GDP growth measures the rate of economic activities in a country. The higher the activities, the higher the growth, job creation, profitability opportunities, lower production costs, among others.

The state of the Nigerian economy does not encourage many firms to list on the bourse. According to the Manufacturers Association of Nigeria (MAN), many of its members provide their own water, power and even infrastructure. Manufacturers’ expenditure on alternative energy sources rose nearly six times between 2014 and 2022, increasing from N25 billion to N142.12 billion over the period, according to MAN.

Businesses are facing multiple taxation that hurt competitiveness. High operations and production costs are stifling businesses in Africa’s most populous nation, making sustainability difficult. More than two million small and medium businesses shut down between 2019 and 2021, according to the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency (SMEDAN).

“You can’t have businesses paying over 100 taxes and you expect them to be healthy enough to list on the stock market,” said a market analyst, Mr Ike Ibeabuchi.

“Also, some companies prefer secrecy to avoid being overtaxed. So, it is also partly a function of your economy,” he added.

A policy expert, Mr Samuel Atiku, said a large chunk of businesses in Nigeria were in the informal sector.

“The majority of businesses in Nigeria are deconstructed from the financial sectors since the country’s economy lacks structure, manpower, and resources. Most businesses do this in other nations because they can obtain loans, but Nigeria needs robust loan mechanisms for businesses. Lack of access to loan and overdraft facilities is another factor in this,” he said.

“Also, due to the lack of rewards or incentives, businesses do not perceive a need to participate in these activities.” Atiku added.

Fewer entrants, more delisting

In December 2019, MTN listed as one of the deepest-pocket firms on the bourse. Airtel Africa, BUA Cement, and Geregu Powerhave also listed in the last three years.

However, there have been tens of exits in the last seven years, including AG Leventis, Costain West Africa, First Aluminium, Evans Medicals, Continental Reinsurance, among many others.

Many foreign portfolio investors have moved on from the Nigerian market. In 2015, foreign portfolio investors’ share of the equity market was 55 percent but it fell to 6 percent by the first quarter of 2023. Local investors have raised their stake from 45 percent in 2015 to 93 percent today, which is also good. However, here lies the problem of retaining investors in the market.

While more firms are delisting from the Nigerian stock market, many are listing on Abu Dhabi market. Eleven firms have listed to raise over $2 billlion in the UAE bourse this year. By February 2023, about 23 Saudi companies were waiting to list on the country’s bourse, according to the local media.

“Companies find no value in the market,” said Unah. “After paying all the fees in the market and you find no value, you delist,” he noted, adding that unless there were incentives to boost firms’ morale, the situation might not change.

Stock enthusiast and investor, Mr David Oke, noted that Nigeria wasn’t ready for stock investments, saying that “the Nigerian stock market doesn’t appear to be ready, and the systems and processes for both investors and companies don’t reflect the readiness of the economy.”

He further said there was no market for people actively seeking to invest in stocks.

A Lagos-based stock market investor, Ms Ada Oranye, fears that if the current trend continues more firms will delist from an already underperforming stock market.

“So, you need to quickly fix the economy because it is only healthy companies that can list. Two, list the NNPC and allow shareholders to determine issues like subsidy and status of refineries. Three, exit all commercial enterprises by listing them and allowing investors to own majority shares. Introduce the NLNG model in running most government entities. If you do these, there will be less headache and investors’ participation will increase,” she noted.

.webp)

.webp)